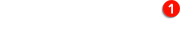

Austerlitz

by Anthea Bell and W.G. Sebald

WG Sebald's Austerlitz has something of the fractured narrative and wanderlust of his novels The Emigrants and The Rings of Saturn, and continues to develop their obsession with history, loss and memory--or more precisely in this case, forgetting. In the decade since the original German publication of Vertigo, Sebald has established himself as indisputably one of Europe's most interesting and lauded writers. In 1967, the narrator bumps into a man in the salle de pas perdus of Antwerp's Central Station. Thus begins a long if intermittent acquaintance, during which he learns the life story of this stranger, retired architectural historian Jacques Austerlitz. Raised as Dafydd Elias by a strict Welsh Calvinist ministry family, it is only at school that Austerlitz learns his true name--and only years later, by a series of chance encounters, that he allows himself to discover the truth of his origins, as a Czech child spirited away from his mother and out of Nazi territory on the Kindertransport. He returns to confront the childhood traumas that have made him feel that "I must have made a mistake, and now I am living the wrong life." In this writer's hands, Austerlitz's tale of personal emotional repression becomes a metaphor for Europe's smothered past. Sebald wittily explores the tricks of time and space, unearthing Europe as an unconscious palimpsest. Delighting in lists and unfeasibly lengthy descriptions, Sebald can turn anything to poetry--even the alleged health benefits of Marienbad's Auschowitz springs become "a positive verbal coloratura of medical and diagnostic terms" (luckily, all his characters seem to be able to hold forth this way). Indeed, Sebald writes with such preternatural lucidity that even a harrowing account of writer's block ironically becomes a celebration of his own quite clearly unblockable virtuosity. At heart, though, Austerlitz is a serious indictment of modern Europe's "avoidance system", its repeated patterns of personal and institutional forgetting that, even within Austerlitz's own lifetime, have contrived to obscure, ignore and render irretrievable his past and the source of his pain. And yet, despite the bleakness of that picture, the book ends with its hero--and its readers--committed to trying, at least, to remember. --Alan Stewart

Release Date:

July 3, 2002